RCM embodies the best aspects of the four main maintenance philosophies.

Maintenance philosophies and practices have been around for many years – the objective of these philosophies being the economics consideration of optimising plant availability in industry. There has been a steady evolution from breakdown maintenance to preventive maintenance to predictive maintenance to proactive maintenance in the quest to keep industrial equipment operating economically, efficiently and safely.

Breakdown maintenance

Thirty years ago it may have been sufficient to adopt a breakdown maintenance philosophy whereby plant management would allow equipment to run to destruction and simply replace it at failure. In today’s economic climate this is no longer viable. Not only does the cost of repair or replacement have to be borne in mind, but the cost of down-time, lost production and safety must be considered. In the majority of cases, it does not make economic sense to manage a plant in this way.

Preventive maintenance

With the increase in the cost of machinery, spares and labour, and the cost of industry of lost or poor production, breakdown maintenance evolved into preventive maintenance in the late sixties and early seventies.

The objective of preventive maintenance was to organise a time-based schedule for service and overhaul of essential equipment. By using preventive maintenance it was hoped to eliminate or drastically reduce component failure and down-time improving productivity and profitability.

Predictive maintenance

Predictive maintenance was a great step in the right direction, but could only take maintenance philosophy so far, in that equipment was being checked, serviced and repaired on a regular basis and that history files were being kept on the equipment. One of the problems with preventive maintenance is that it is possible to over-maintain equipment; the cost of maintenance must be balanced against the cost of breakdown. This led to a shift from preventive to predictive maintenance.

The concept of predictive maintenance is to carry on with the planned preventive maintenance but, at the same time, conduct as many non-destructive tests on the items of plant to determine their mechanical integrity. Basically, this philosophy asks the question, “What is the point of fixing something that isn’t broken?” Oil analysis is probably the cheapest and easiest form of predictive maintenance to implement, but other techniques include vibration analysis, thermographic imaging, motor current analysis, balancing and alignment. It may be found that some failure modes cannot be detected by oil analysis on certain equipment, for example on non-lubricated components such as electric motors. In these cases other techniques must be employed.

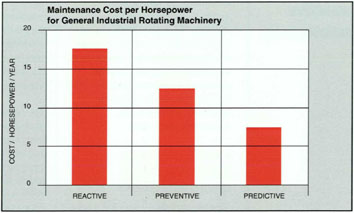

The bar chart below shows the maintenance costs for general industrial rotating machinery, comparing reactive (breakdown), preventive and predictive maintenance philosophies.

Studies have shown that a successful preventive maintenance programme can provide a 30% reduction in maintenance costs over a breakdown maintenance programme.

One important aspect of a predictive maintenance programme is that plant is not overhauled unnecessarily.

Contrary to popular belief, there is not a strong relationship between operating age and reliability. Once a piece of equipment has “bedded-in” and established a reliable operating mode, overhaul will disturb this mode and research has shown that the overhauled component will not last as long as the new component. If the predictive maintenance techniques employed do not indicate a problem, then don’t disturb a stable and reliable operating mode.

With the introduction of predictive maintenance and accurate record-keeping in machine history files, certain failure modes can be determined and this leads directly to a proactive maintenance philosophy.

Proactive maintenance

Proactive maintenance looks at root cause failure analysis (RCFA) to determine the cause of certain common failures in industrial equipment. If the cause of failure can be determined, can that cause be eliminated? Whereas previous maintenance philosophies have looked at predicting the failure of a component and taking action before the failure actually occurs, proactive maintenance looks at the root cause of failure and aims to eliminate the cause so that, in turn, that failure mode is also eliminated.

A good example of using RCFA in proactive maintenance is the influence of particulate contamination in the failure of fluid power systems. Research has shown that 70% - 85% of hydraulic component failures are due to particulate contamination, with up to 90% of these failures due to abrasive wear.

Predictive maintenance has established the cause of the majority of hydraulic system failures; the object of proactive maintenance philosophy is to eliminate that cause by keeping hydraulic fluids as clean as is practically possible. By regularly checking the cleanliness of hydraulic fluids, a large number of hydraulic component failures can be prevented.

Oil analysis forms an important part of proactive maintenance. In the example cited above, oil analysis is used to determine the cleanliness levels of lubricants so that dirty oils can be either cleaned or changed when unacceptable levels of contamination are detected. Although oil analysis is strictly part of predictive maintenance, it can also be instrumental in RCFA and can lead to good proactive maintenance practices. For example, oil analysis could be used to predict bearing failure in an automotive application. If the engine can be dismantled before actual failure then, firstly, subsequent damage can be avoided and, secondly, it is hoped that the cause of the bearing failure can be determined. This is particularly useful when one considers that certain failure modes, at the point of failure, can destroy the evidence of the cause of failure. In this way oil analysis can form an integral part of proactive maintenance.

Reliability-centred maintenance (RCM)

A lot of large industrial organisations have adopted the concept of RCM which encompasses all the best aspects of the four basic maintenance philosophies discussed above. Even breakdown maintenance has its benefits in certain applications (replacing a burnt out light bulb, for example)

The introduction of RCM to a company or organisation is not something that can be carried out overnight and the benefits are not likely to be immediately quantifiable. What is most important is that the company must have a maintenance philosophy or mission statement and a top-down management commitment to that mission statement. Only then can a RCM system be developed or expanded from existing maintenance systems. Management must be involved at all levels with regard to decision-making in the maintenance department before an effective maintenance philosophy can be implemented.

General acceptance of an RCM group by the workforce can sometimes be one of the biggest hurdles to overcome, because the maintenance planning department is frequently seen as a “police force” checking up on quality of work carried out by the artisans in the plant.

However, once an RCM programme has been instituted, developed and receives the full support of management and the workforce, then the company can look forward to dramatically increased reliability, productivity and safety as well as the ultimate benefit: increased profitability.

For more information contact WearCheck on +27(0) 31 700 5460 or This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.