There are certain things in life that improve with age. Wine and whisky develop deeper, more complex flavours. Bonsai trees mature into highly valued works of art and even acoustic guitars and violins are said to improve in tone as the wood ages and the instrument opens up.

Unfortunately, the list of things that don’t improve with time is far longer. Our physical health declines, sometimes along with our sense of humour. Metals corrode, paint fades and, perhaps less romantically but more relevantly, lubricants also age.

Unlike wine or instruments, however, lubricants are not designed to get better with age.

Lubricants rarely fail suddenly. They don’t just wake up one morning and decide to stop working, and they don’t usually announce the end of their useful life with dramatic symptoms. Usually, a lubricant quietly ages, reacts, and is slowly consumed by the environment in which it operates. By the time a problem becomes obvious, the oil has usually been struggling for some time. This is what we mean when we say, “when good oils go bad”.

A lubricant doesn’t become “bad” simply because it has darkened, developed an odour or been in service for a period of time. These changes are often early symptoms of degradation, but they do not, on their own, define failure. A good oil goes bad when it can no longer perform the functions it was designed to perform. So, what is a lubricant actually supposed to do?

|

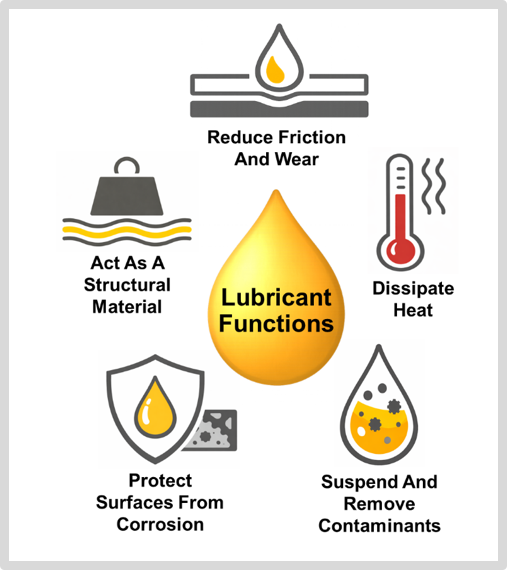

A fully formulated lubricant is far more than just “oil.” It’s a carefully balanced blend of base oils and additives designed to perform several critical functions all at the same time. While the specific functions vary by application, they generally fall into five fundamental groups. Firstly, lubricants are used to reduce friction and wear between moving surfaces. By maintaining a protective film, the oil limits metal-to-metal contact and helps prevent mechanical damage. Secondly, lubricants play a vital role in dissipating heat. As machines operate, friction, load, and in some cases combustion, generate heat that must be removed from critical components. The lubricant acts as a heat-transfer medium carrying thermal energy away from high-temperature zones. |

|

Thirdly, lubricants are expected to remove and suspend deposits. Contaminants like wear debris, soot and oxidation by-products must be kept in suspension and carried away from sensitive surfaces so they can be removed by filtration or oil changes.

Fourthly, lubricants are formulated to protect metal surfaces from corrosion and chemical degradation. Additives are included to neutralise acids, inhibit rust and prevent chemically aggressive species from attacking machine components.

And finally, a lubricant acts as a structural material. Viscosity, film strength and load-carrying capacity determine whether the oil can physically separate surfaces under operating conditions. If the oil film collapses, the lubricant can no longer do its job.

As long as a lubricant can perform these functions, it is still “good.” When one or more of these functions is compromised, the oil may still be present in the system, but it is no longer fit for purpose.

From degradation to lubrication failure

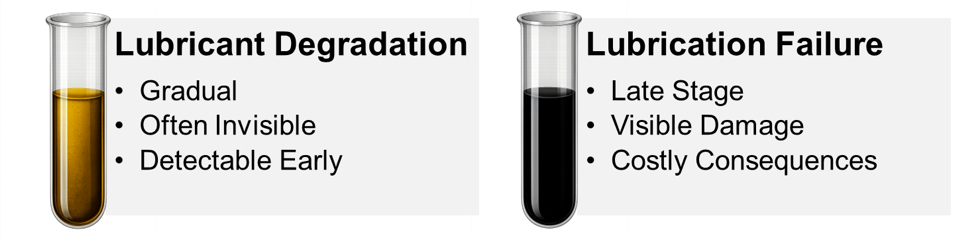

Lubricant degradation is often the first step on the path toward lubrication failure, but the two are not the same.

Degradation refers to the gradual chemical and physical changes that occur in an oil during service. Additives are consumed, base oils react with oxygen, contaminants accumulate and operating stresses take their toll, yet - initially - these changes may not significantly affect machine operation.

Lubrication failure, however, occurs when degradation has progressed to the point where the oil can no longer protect the equipment. At that stage, wear rates increase, temperatures rise, deposits form, corrosion accelerates and component damage becomes likely.

The critical distinction is that degradation begins long before failure becomes visible or irreversible. Understanding this gap between degradation and failure is what allows corrective action to be taken in time.

This is where oil analysis plays a vital role - not as a post-mortem tool, but as a means of detecting lubricant degradation early while intervention is still possible.

Why do oils degrade at all?

Even the best lubricant operating in well-maintained equipment under favourable conditions has a finite life. Oils degrade because they are continuously exposed to stresses that slowly change their chemistry and performance.

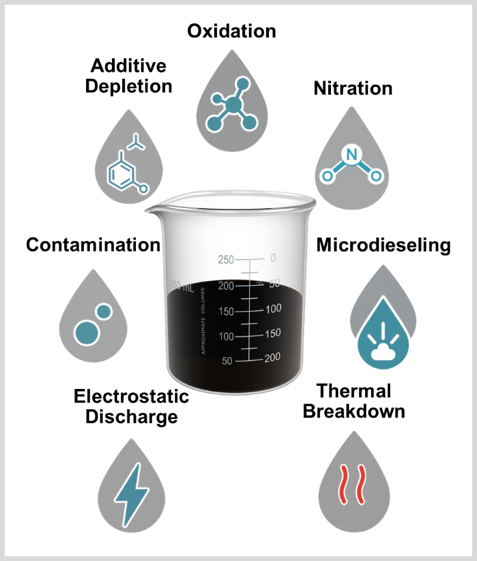

Heat accelerates chemical reactions while oxygen drives oxidation. Contaminants such as water, fuel and soot interfere with additive performance and promote further oil degradation, and mechanical stresses can break down polymeric additives like viscosity index improvers. Over time, the very additives designed to protect the oil and the machine are consumed doing their job.

|

What is important to note is that these processes do not occur in isolation. Multiple degradation mechanisms are usually active at the same time interacting with and accelerating one another. This is why lubricant degradation can be difficult to interpret without understanding how and why these changes occur. In this WearCheck series, When Good Oils Go Bad, we will explore the main ways lubricants degrade in service and how these degradation modes affect oil performance and machine reliability - from oxidation and nitration to thermal breakdown, microdieseling, electrostatic spark discharge, additive depletion and contamination. |

|

By understanding how lubricants degrade, it becomes easier to interpret oil analysis results, identify emerging risks and make informed maintenance decisions. After all oils don’t die - they degrade, and the earlier we understand that process, the better we can manage it.

Like people, lubricants age whether we notice it or not - the difference is that with oil analysis, at least the oil can’t lie about it.

Look out for the next instalment of this series.