The ABC's of oil by John Evans, Diagnostics Manager, WearCheck.

When purchasing a can, drum or tankerful of oil, how can you be sure of what you are buying, where you can use it, and what quality you are getting for your money? On every can of lubricating oil there is (or should be) a series of numbers and letters that describe what is inside. This article will look at what those numbers and letters tell you.

Oils have both physical and chemical properties. They consist of a ‘base stock’ which is refined crude oil blended with various ‘chemicals’ that impart desired properties to the lubricant enabling it to perform its job.

Let’s look at the physical properties first:

The most important physical property of an oil is its viscosity. Viscosity is defined as a fluid’s resistance to flow, under gravity, at a specified temperature. What that simply means is - ‘how thick is the oil?’ Thick oils do not flow so easily and have high viscosities, thin oils are quite fluid and have low viscosities. Think how differently compressor fluids behave when poured, compared to gearbox oils.

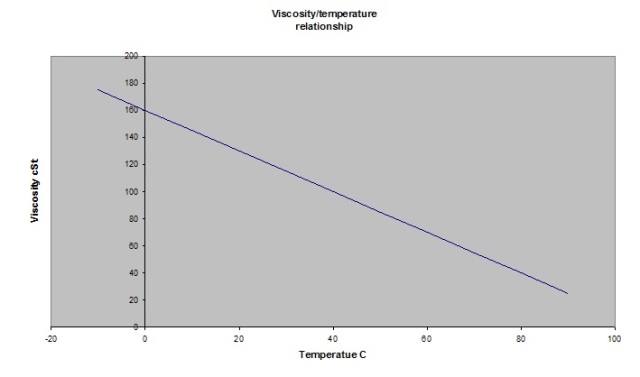

The actual property of interest is called kinematic viscosity, its units are known as centistokes and one centistoke is one millimetre squared per second. It is important to remember that as temperature increases, the viscosity of an oil decreases.

The SAE or Society of Automotive Engineers has a grading system that describes the viscosities of oils that are used in all automotive applications from motor scooters, family cars and4X4s to buses, trucks and bulldozers.

There are two parallel systems, one for engine oils and one for gear oils. The number and letters associated with the SAE system are shown below.

The reason for two systems is that gear oils have very different chemical properties to engine oils as they have to perform different functions. You might get away with putting an engine oil in a gearbox but you certainly won’t do your engine any good by putting in a gear oil. If it is a big number (more than 60) it is a gear oil, if it is a small number (less than 70) it is an engine oil. This is to avoid confusion. It is important, however, to note that both series cover the same range of viscosities. An SAE 30 engine oil is just as thick as an SAE 85W gear oil.

You will note that some of the grades have a ‘W’ after them, these are the lower or thinner grades that function better at low temperatures as all oils will be thicker when they are cold. These grades can also be blended with other non-W grades to form what are known as multigrade oils. Monograde oils have such designations as SAE 10W or SAE 90 whereas the multigrades have names such as 20W50 or 80W90. Remember, if you increase the temperature of an oil you will decrease its viscosity; a temperature viscosity graph may look like this:

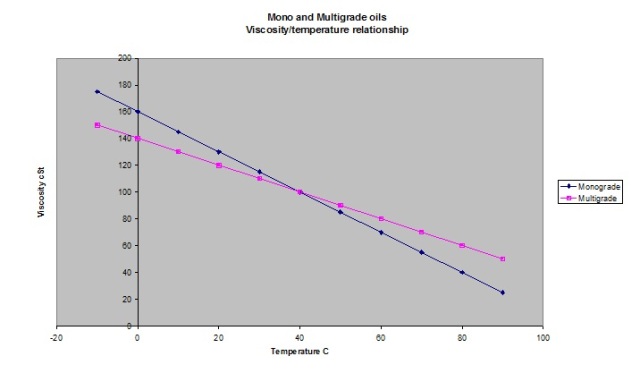

On a very cold winter’s morning, the temperature might be as low as -10 degrees Celsius; but at operating temperatures, the engine will have heated the oil to 90 degrees Celsius. Ideally,you require a fairly thin oil that will flow at low temperatures but doesn’t thin out too much as the engine reaches operating temperature. Multigrade oils are formulated to perform under exactly these conditions as they thin out less than monograde oils when they are heated. The following graph is an exaggerated illustration of how the two types of oils behave:

The advantage of using a multigrade oil is that its viscosity is more stable over a greater range of temperatures. In effect, a 20W50 will behave like an SAE 20W when it is cold and an SAE 50 when it is hot providing protection for your engine over a wide range of conditions. The ‘W’, in fact, stands for “winter".

Well, that has dealt with the physical properties of the oil, but what about the chemicals that are added to the base stock in order for the oil to do its specific job? In other words, if I buy a can of oil, how good is it?

More to follow in part 2 of The ABC’s of oil.